Explore. Connect. Excel.

Constitution for the USA: An Introduction

Take the Quiz

Articles of Confederation

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted to declare their independence from the British Empire. Two days later, the Declaration was officially adopted. However, the newly formed United States still had not settled on the details on how the system would operate. It was over a year after declaring independence before America's first constitution was completed in 1777 and another three and a half years until it went into effect in 1781. After finally ratifying the Articles of Confederation, it wasn't long before it became clear the new system was failing.

The new constitution was largely a reaction to the centralized power of the British system, and the pendulum had swung too far the opposite direction. The new United States government had no power to levy taxes, so it was perpetually broke. Other countries were reluctant to lend money to the U.S. considering its inability to secure funding. The U.S. government couldn’t raise a military. It didn’t print money or represent the states with a unified voice internationally. States printed their own money and signed their own agreements and treaties with other countries. The confederation’s central government also couldn’t regulate trade among the states. Trade wars started between states as a result.

Constitutional Convention

By the spring of 1787, American leaders had admitted failure and a constitutional convention in Philadelphia was called to repair the Articles of Confederation. Pretty quickly, they determined the best route was to start over. The convention ended a few months after it started, and the new constitution had been created, but it wasn’t ratified and in effect until 1789.

Compromises: Several issues surfaced immediately beside the fact that the national government was toothless. Under the Articles, each state had one vote. States with large populations like Virginia and Pennsylvania didn’t appreciate having no more influence than smaller states like Delaware and Rhode Island.

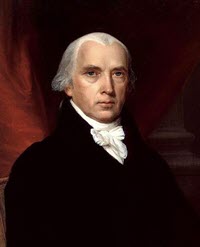

James Madison put forth “The Virginia Plan” which wasn’t all that different from what the U.S. system looks like today. That included a federal government with three branches and a bicameral legislature. It included a legislature to make laws, an executive to implement them, and a judiciary to settle disputes over laws, which is how the United States is constructed today. The key difference was that the representation in the House and Senate would be based proportionally on the population of the states.

This didn’t sit well with delegates from the smaller states. William Paterson introduced “The New Jersey Plan,” which looked much like the Articles, but with a stronger central government. Under this plan, like under the Articles, each state would have equal representation in a unicameral chamber. It became known as “The Connecticut Compromise,” which is the system today where each state has equal representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House of Representatives. The Electoral College was another compromise based on the same principles of protecting smaller states while allowing larger states more power. Each state receives a number of electors equal to their number of members of Congress (Senators and Representatives combined). The Electoral College keeps the states in charge of choosing the president, but the larger states have more influence. The purpose was to disallow major cities from outvoting entire states, and it succeeded in convincing small states to join the new union.

A very contentious debate resulted in the “Three-fifths Compromise.” How would slaves and Native Americans be counted when determining population and allotting congressional and electoral representation? Delegates from northern states wanted free citizens to count when allotting representation. Southern delegates came from states that had smaller populations even when slaves were included. They were concerned that the northern states would call all the shots and threatened to walk out of the convention if their slave populations were not included when counting population. What resulted is one of the most infamous aspects of the United States’ founding documents. Only three-fifths of the population of slaves would count, essentially counting each slave as only 60% of a person.

Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 still reads today:

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

Even though the Three-fifths Compromise was made obsolete when the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments freed slaves and made them American citizens, it is still a relevant aspect in discussion on civil rights in contemporary America.

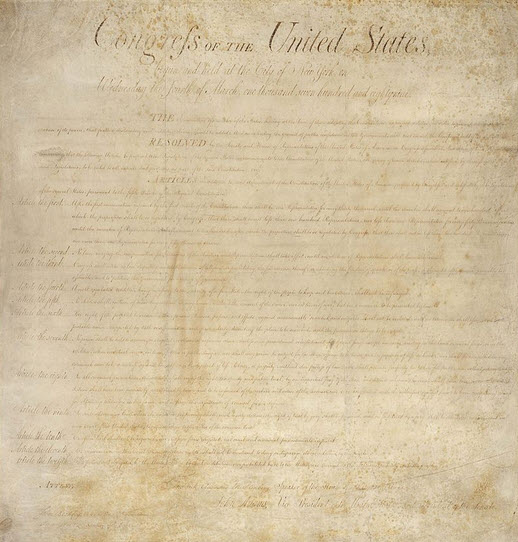

Bill of Rights

Although the Constitution makes no mention of a two-party system, the United States was settling into one before the Constitution was even ratified. “Federalists” were those in favor of the new system, and they later became known officially as the Federalist Party. “Anti-federalists” opposed it and went on to form the Democratic-Republican Party, who later became today’s Democratic Party. It was the Federalists, like James Madison, who supported the new constitution.

Anti-federalists still had a great influence on the Constitution as it is today. Having combed through it, they found holes in the new system. Mistrusting of a strong and centralized government, part of the deal to get support for the new system was the Bill of Rights, which are the first ten amendments. The purpose was twofold. First, it clearly laid out rights that Americans had that the new federal government would not be allowed to curb, such as freedom of speech, the right to own weapons, the right to a trial by jury, and protection from unwarranted searches and seizures of property. It should be noted that while Amendment I prohibits an official state religion, like the Church of England, it never mentions a “separation of church and state.”

It went two steps further though. Amendment IX says, in plain terms, that the rights listed in the Bill of Rights are not exhaustive. That means Americans have other rights not listed in the Bill of Rights, even if they couldn’t think of them at the time such as the right to privacy. Amendment X bolsters the Constitution’s limit on federal power and basically says that the federal government only has the powers listed in the Constitution. If the Constitution doesn’t explicitly say the federal government can do it, then it can’t. That may leave some questions as to how the federal government regulates healthcare or provides welfare programs when the Constitution makes no mention of such powers. POLS210 American Government is good place to learn more about how the federal government has grown beyond its original boundaries.

Subsequent Amendments

Article V of the Constitution lays out the processes for revising or adding to the Constitution. The founders realized that there was no way to anticipate all the future circumstances the United States would encounter. To ensure that changes could be made when necessary, essentially two different methods were included.

- Congress can pass an amendment through both chambers by a two-thirds vote. Afterwards, three-fourths of the states must ratify, or approve, of the amendment.

- Two-thirds of state legislatures can call for a “convention of states,” or rather a new constitutional convention like the original one of 1787. Any number of amendments can be approved at such a convention, including a complete rewrite of the Constitution. Then three-fourths of the states would have to approve of the changes. This method has never been used.

The Constitution has been officially amended 27 times, but for practical purposes there have been 15 substantial changes to the original document. Remember that the first ten amendments were included in the Bill of Rights, which were a packaged deal with the new Constitution. Of the remaining 17 amendments, two of them are a wash. The 18th Amendment outlawed alcohol. The 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment, leaving the U.S. back where it started.

Here are those 15 amendments and what they accomplished.

Amendment XI

This prohibited people who lived outside a state from suing that state. It laid the groundwork for “state sovereign immunity,” which shields states from being sued. For example, if a business went bankrupt because the state cranked up taxes or the governor issued a stay-at-home order due to a pandemic, that business wouldn’t have standing to sue the state for damages.

Amendment XII

This changed election of the vice president to run on a ticket with the presidential candidate. The original system made the second-place candidate the vice president. Imagine Hillary Clinton as Donald Trump’s vice president, and it becomes clear why the original system didn’t work well back then.

Amendment XIII

Slavery was outlawed.

Amendment XIV

Made former slaves into American citizens.

Amendment XV

Guaranteed the right to vote for men who were former slaves.

Amendment XVI

Allowed the federal government to collect income taxes.

Amendment XVII

Senate elections were changed to direct popular vote. Prior to this, the state legislatures chose their Senators.

Amendment XIV

Expanded voting rights to women.

Amendment XX

Changed the date of presidential inauguration and stated that the vice president would become president if the presidency is vacant.

Amendment XXII

Presidential terms were limited to two, with the exception of a president potentially completing the final two years of a predecessor’s term and then serving two more terms. This is why the maximum number of years one can be president in the U.S. is ten years.

Amendment XXIII

Residents of Washington D.C. were granted a voice in presidential elections

Amendment XXIV

Outlawed poll taxes and other financial requirements to vote.

Amendment XXV

This clarified and detailed presidential succession on the heels of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Amendment XXVI

The voting age was lowered to 18. This is the most recently proposed and successful amendment, and it was back in 1971.

Amendment XXVII

Congressional salary raises don’t take effect until a new Congress is sworn in. This was originally proposed along with the Bill of Rights. Three-fourths of the states failed to ratify it, but no expiration date was ever attached to it. A college student wrote a paper in 1982 claiming that this could still be ratified. He was right, and in 1992 it became the most recent amendment to the Constitution over 200 years after it was first proposed.

Judicial Review

The amendment process is lengthy and difficult. The convention of states method has never been used. Finding two-thirds votes in both chambers of Congress has been virtually impossible in a Congress so partisanly divided that continuing resolutions regularly replace actual congressional budgets. Yet, the Constitution does still manage to change with the times through judicial review.

Although such a power of the Supreme Court is not clearly stated in the Constitution, it was assumed to exist. In the 1803 Marbury v. Madison Supreme Court decision, the Supreme Court asserted its power to strike federal and state laws and executive actions that were in conflict with the Constitution or “unconstitutional.” This power of judicial review has reinterpreted and clarified parts of the Constitution, especially in areas that were not even considered during the era of the founders. These include issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, and electronic surveillance of citizens.

Segregation is an issue over which the Supreme Court fully demonstrated the power to revise the Constitution without changing a word in it. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racial segregation did not violate the Constitution. However, the constitutional issue of segregation based on race was not settled permanently by this decision. In 1954, the Brown v. the Board of Education Supreme Court decision turned the Plessy decision on its head. In a unanimous decision, fewer than 60 years later, the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was a flagrant violation of Amendment XIV’s “Equal Protection Clause.”

Judicial review is a powerful tool. With the amendment process sitting idly for decades, it is the primary method to address constitutional issues. This is why Senate confirmations of appointments to the Supreme Court have gone from essentially a formality to full-blown political battles. It is not coincidence that 1971 was the last successful amendment, and the partisan fights over appointments began in the 1980s.

Original Intent vs. The Living Document

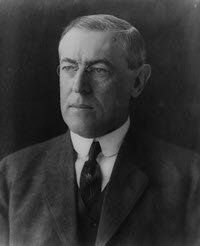

One of the most divisive arguments over the Constitution has been the concept of original intent versus the view of the Constitution as a “living document.” One of the first mentions of this philosophy was in Woodrow Wilson’s book Constitutional Government in the United States, where he referred to “living political constitutions.”

The “living document” approach takes a view that the authors of the Constitution and its subsequent amendments, which were written over a century later in some cases, couldn’t foresee future circumstances. It’s up to the courts to apply the concepts of free speech and the right to bear arms to the changing technologies of the day. The founders could never imagine, for example, the issue of the National Security Agency monitoring all emails, texts, and cell phone calls. These issues arise in the courts regularly, and it’s not realistic to believe the slow-moving amendment process can keep up with them. The “living document” philosophy allows flexibility for the country to change with the times. For example, the Constitution says only the Congress can declare war, yet it’s become accepted that the president can order military actions as long as they’re not officially declared as war.

The original intent philosophy relies on a stricter interpretation of the text of the Constitution. When changes need to be made to the Constitution, it has a built-in process to do so. It doesn’t need judges to make changes as they see necessary. After all, if the Constitution says whatever a majority of the Supreme Court says it says, then there’s no point in having a Constitution. Those who favor originalism point to the writings in the Federalist Papers, where the Constitution’s authors went into great detail explaining exactly what they meant in the Constitution. For instance, details about the intent of “federal supremacy,” which means the federal laws trump state laws when they conflict, can be found in Federalist #33.

The Constitution Today

Even though it’s often referred to as the cornerstone of American democracy, the word “democracy” appears nowhere in the Constitution. Views on the Constitution today spread across a vast continuum from one polar extreme to another, with most Americans falling somewhere in the middle. Some see it as the most ingenious and important document created by people in history, which is why it is the world’s oldest surviving constitution. It gave rise to the world’s greatest superpower, ended slavery, promoted equal rights, and continues to serve Americans well. Others see it as an antiquated relic of a past tainted by racism and sexism, written by rich white men so it only serves rich white men. Regardless of the views one may hold on the Constitution for the United States, there’s no denying the relevance of the document in American life.

References

National Archives. 2019. "Constitution of the United States - A History" https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/more-perfect-union

National Archives. 2020. "The Constitution of the United States" https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution

National Archives. 2020. "The Bill of Rights" https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights

Wilson, Woodrow. 1908. Constitutional government in the United States. New York: The Columbia University Press https://www.loc.gov/item/08017752/