By Evan Rosenberg, MS, JD, | 07/11/2024

When it comes to emergency management preparedness and prevention, there is certainly no shortage of disasters. From increases in the strength and frequency of major storms to escalating drought conditions leading to major wildfire activity, natural disasters are becoming more severe and more commonplace in our nation.

In addition to natural disasters, an uptick in man-made disasters, such as cyber-attacks, chemical spills, and mass shootings, has prompted emergency managers to prepare for an endless number of scenarios in their communities.

However, being ready for such events in one's community requires much more than developing immediate response plans. National preparedness and response efforts involve addressing potentially long recovery times for the impacted area, which is where the real work of emergency management happens.

A Fundamental Flaw in Emergency Management

After multiple hurricanes struck my home state of Florida, I was surprised by the amount of confusion and uncertainty that surrounded the management of response and recovery operations in my community.

After all, my state is Florida, a state that has experienced numerous major disasters. Why would a place like Florida, which should be accustomed to severe weather and recovery procedures, continue to stumble in this area?

One possible answer lies in a fundamental flaw in the emergency management (EM) field as it is taught today.

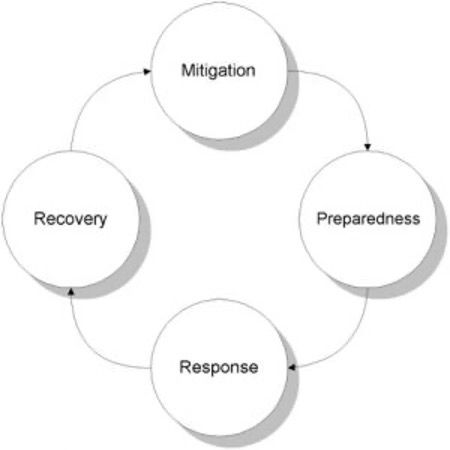

The Emergency Management Lifecycle

People involved in emergency management are likely familiar with the “Emergency Management Lifecycle” diagram, which includes four phases in a continuous cycle. This diagram shows the cyclical nature of emergency management. There is preparedness, recovery, and mitigation, which then completes the circle by returning as a lead-in to preparedness again.

Image courtesy of FEMA, IS-111 Course Training Materials, Unit 4

When I was thinking about why our nation fails to plan properly for recovery operations – at least when we compare that to the amount of attention we give to preparing for response operations – this oversimplified diagram immediately jumped out as one of the problem areas.

Basically, we train people to think that preparedness is all about incident response, but this way of thinking could not be further from the truth. In a perfect world, preparedness would feed into each of the other three phases, not just response.

Granted, it is true that response is generally the most publicly visible phase of the emergency management lifecycle. It is the phase where everyone is in a “rah-rah” mood, with superiors and elected officials striving to telegraph the appearance that everyone is on the same team and working toward the singular goal of response.

Daily reports trumpet the number of homes that have had power restored, the number of survivors who have been assisted by search and rescue teams, and even the simple arrival of additional utility work crews from other states to ensure effective coordination.

The Reality of the Response Phase

As long as we sense that the cavalry is here or at least on the way, we can see the eventual end to response activities and the end of the disaster.

But in reality, the response phase lasts for a very short period of time. After a few days or weeks, the shift to the potentially decades-long task of recovery begins, emphasizing the need to plan ahead and create programs for effective long-term recovery operations.

Key missteps in the very beginning of recovery operations can come back to haunt you years down the road, so it’s crucial to plan carefully and diligently execute those plans from the start.

A Disproportionate Focus on Response Plans

Given that reality, why do emergency managers write volumes full of plans for response procedures, especially considering that first responders already have their own plans and procedures? Meanwhile, they only write a couple of pages about recovery.

Even for those “enlightened” emergency management departments that take recovery more seriously, the resulting recovery plan is typically full of general statements, unclear lines of responsibility, and a lot of “buck passing” where some higher level of government (i.e. the state, FEMA, or some other organizations) is assumed to be on the way to run recovery efforts.

20 Questions for All Local Emergency Managers

As a practitioner who spent his whole emergency management career focused on recovery operations, I think it is time to open the dialogue about how we, as an industry, can better plan for long-term recovery.

To that end, here is a starter list of 20 questions that local emergency managers can read and review against their current recovery plans. If most of these questions are not answered with a "yes," it's a good starting point for plan revisions.

- Do we have an inventory of all publicly owned property (land, real estate, equipment, vehicles, and furniture) along with current estimated valuations? Are these items reflected in our governmental insurance policies for both property and flood insurance?

- Do we have an up-to-date staffing plan that includes the names of specific individuals for a dedicated recovery section in the emergency operations center during incident response operations?

- Do we have a current staffing plan that includes the names of people and contact information of recovery functional leads from all sub-entities within our local government? This plan should include contact information for individuals from each governmental unit who will be leading efforts once we move into recovery.

- Have we remembered to include the private sector in our recovery plans? Do we have a contact at the Chamber of Commerce or a similar entity who will act as a liaison between the private sector and government?

- Does the local government have a communications plan and a dedicated public information officer (PIO) to keep the public aware of how recovery is progressing? This person is also responsible for getting the word out about deadlines, meetings, and other essential information.

- Do people in the emergency management department have a communications plan in place to keep elected officials informed of how we are progressing? This plan must also include ways to funnel questions, data requests, and similar requests back to the department.

- Have we estimated how much help we should realistically expect from the state and/or federal governments? What will our cost-share be for that help, both in the response and recovery phases?

- Do we have the monetary reserves necessary to pay this state/federal cost-share? If not, how do we expect to raise these funds?

- What is our plan for using stand-by and emergency contracting? Have we ensured that these plans meet federal procurement regulations? (Remember that the Governor’s Executive Order(s) can waive state requirements but cannot waive federal requirements.)

- Do our current, day-to-day contracts for services meet federal procurement regulations?

- Do we understand what is eligible for reimbursement under federal (and possibly state) recovery regulations?

- What exactly do we have to do at the local level to get our county included in a federal disaster declaration?

- Do we have an updated staffing plan, which includes names of people and approval from their day-to-day work units for teams to conduct initial damage assessments, especially in areas at greatest risk, as well as to work with FEMA on preliminary damage assessments?

- Do we understand how to classify damage to homes using FEMA’s Individual Assistance categories?

- Do we have the name of a dedicated person who will be collecting costs that may be eligible under FEMA’s Public Assistance program?

- Does our accounting/timekeeping system allow for the entry and storage of separate time records for employees, both for time spent working on the disaster (and their specific duties/tasks), as well as time spent working on non-disaster duties/tasks?

- Do we have a plan for capturing and reporting the value of volunteer hours and/or donated resources?

- Do we have an agreement with the state for debris pickup and/or repair work on state roads/facilities (buildings, parks, and state submerged lands) within or passing through our physical jurisdiction? This plan should include who is responsible for what tasks, who pays for what, and who requests reimbursement from FEMA.

- If the emergencies cause a housing crisis, what regulations do we plan to relax to allow for the long-term sheltering of citizens within our jurisdiction?

- Do we have a plan in place for regular and continued auditor/inspector general scrutiny of disaster finances?

This list is just a starting point to help local teams assess their level of preparedness for recovery operations. However, it is important to note that even the most prepared jurisdictions will encounter challenges at the onset of recovery.

Thinking through many of these issues in advance and collaborating with other agencies and entities will enable local governments to quickly recover from any stumbling blocks during recovery operations.

FAQs about Emergency Preparedness

What are the four levels of emergency preparedness?

- Mitigation: Mitigation involves efforts to reduce the impact of disasters before they occur. Mitigation activities can include building regulations, zoning laws, and public education campaigns designed to reduce risks from potential hazards such as severe winter weather.

- Preparedness: The preparedness phase is all about planning and preparing for potential emergencies. At this phase, professionals are developing emergency plans, conducting drills and exercises, training personnel, and ensuring that resources and equipment are available and in good condition.

- Response: Response examines the actions taken during and immediately after a disaster. The goal of the response phase is to ensure safety, implement emergency assistance, and reduce further damage. Response efforts include emergency medical care from different organizations, search and rescue operations, and providing shelter and supplies to affected populations.

- Recovery: This phase aims to restore an affected community to its former state. Recovery operations include repairing and rebuilding infrastructure, providing financial assistance to individuals and businesses, and offering psychological support to victims. This phase can be long-term, depending on the extent of the damage.

What are examples of emergency preparedness?

Emergency preparedness involves using a set of preventative measures and actions to reduce the effects of disasters and emergencies, ensuring a coordinated and effective response. Here are some examples of ensuring preparedness in U.S. communities:

- Creating emergency plans: Developing detailed plans for different types of emergencies, outlining steps for evacuation, communication, and safety procedures.

- Conducting preparedness drills and training: Regularly practicing emergency drills and training sessions for employees, students, or community members to ensure everyone knows what to do in case of an emergency.

- Educating the public: Providing information and resources to educate the public about how to prepare for disasters, how to stay safe during various types of emergencies, and what to do when hazards like wildfires or road floods are encountered.

- ·Controlling disease outbreaks: Effective disease control is also a critical aspect of emergency preparedness, particularly in densely populated areas, where older adults and other vulnerable populations are at the greatest risk.

What are some examples of man-made disasters?

Man-made disasters are events caused by human actions that result in significant damage, loss of life, and environmental impact. Some examples include:

- Industrial disasters – chemical spills and nuclear power plant accidents

- Transportation accidents – train derailments or airplane crashes

- Structural failures – bridge, building, or dam collapses, or infrastructure failures

- Environmental pollution – hazardous deforestation, waste dumping, oil spills, and industrial pollution

- War and conflict – acts of terrorism and chemical, nuclear, biological, and conventional warfare

- Cyber attacks – data breaches or ransomware attacks on critical infrastructure

- Social unrest – riots, mass shootings, and organized crime

Emergency and Disaster Management Degrees at AMU

American Military University (AMU) offers three degrees in emergency and disaster management, including:

- An online bachelor’s degree in emergency and disaster management

- An online master’s degree in emergency and disaster management

- A dual master’s degree in emergency and disaster management and homeland security

These programs are designed for professionals seeking job opportunities in the emergency management fields. Courses in these programs cover topics such as disaster response, risk assessment, emergency planning, mass casualty management, crisis action planning, and strategic policy development.

For more information about our degree programs and certificates, visit our program page.

Evan Rosenberg, MS, JD, spent eight years working in recovery for the Florida Division of Emergency Management, with four of those years as the State Recovery Chief. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering, both from the University of Maryland College Park. Evan also has a master’s degree in urban and regional planning and a J.D. in law, both from Florida State University.

A nationally known expert on recovery and the Stafford Act, Evan spent two years leading NEMA’s PA & IA Subcommittees, under the auspices of the NEMA Response and Recovery Committee. Evan has served on a number of FEMA-industry workgroups.

Since 2012, he has been an adjunct professor at American Military University, teaching courses in emergency and disaster management. Evan left the Florida Division of Emergency Management in 2017 and is currently an executive with the Florida Housing Finance Corporation, where he works on multi-family affordable housing issues in both disaster and non-disaster settings.